the harmony of

wind and waves – why does my old heart

still sing your songs?

All Posts

late spring

Sunlight infiltrates

the blinds. A mourning dove coos.

Life! – for one day more

waking up

deeply dreamt dreams

someday one will just

continue on…

closing

closing night:

lights fade on another

little death

april

winter blowdown;

how many more

springs remain?

carcass season

beaks buried blood-deep

vultures pick their dinner clean;

crows linger in line…

![]()

The Summer Theatre Died – Part Four

Dunkirk NY – At first, I thought this next post in the series was going to be about the future of theatre as I see it. But it occurred to me that writing about the future is somewhat pointless if one does not have as a reference point the present state of theatre. So with that, here is a short but sweet post about the present theatrical situation as I see it.

As a prelude, let me say that I will be writing in broad generalizations and considering apparent trends. Some of what I will mention will be extrapolated conclusions from the 2022 SPPA. Other observations will come from news stories I have read. Little of it will come from direct experience, as my personal experience comes from my work in the Buffalo theatre community, which surprisingly continues to survive and even thrive (the last Artie Awards ceremony this past June sold out a 600-seat theatre). Real data is truly scarce in the theatre world, and so I will make do with what my limited resources allow me to perceive.

To begin with, I think there is no question that in 2023, theatre is struggling. Beginning in March 2020, when the pandemic hit and institutions everywhere and of every kind shut their doors, theatre was hit with a perfect storm. The pandemic closed theatres and thus their source of revenue; the social movements for diversity and inclusion began to infiltrate theatre at several levels, and the nature of theatre leadership began to change. It was an onslaught that nobody was prepared for, and it hit like a ton of bricks. Taking these three broad categories as our entry points, we can dig a little deeper into each category and check out how these events induced change and the struggle it wrought.

First, money. This one is easy. Once theatres closed and ticket sales vanished, theatre organizations were forced to cut staff, reduce shows, and beg for financial support (to the tune of millions and millions of dollars). This situation is ongoing. Most theatres today are struggling to re-capture their level of ticket sales from late 2019. Many have only gotten to the 50% mark. Many other theatres have outright closed shop. Several went into hibernation, suspending their operations until their finances could catch up. Other theatres have survived only because they have been able to raise large sums of money. Oregon Shakespeare Festival raised $9 million dollars over two campaigns to keep its doors open. Recently TheatreWorks Silicon in the San Francisco Bay Area raised $4 million to keep its doors open. But not all theatres can do that. It is becoming more and more apparent that the cost of producing a show continues to rise, as do ticket prices. In this inflationary period, however, less and less people can afford the cost of a ticket, and the breaking point where ticket prices are too expensive for all but the top 5% of earners butts up against the inability to earn enough income to meet costs of production is close at hand, if not already here.

Second, the cultural movement behind the notions of inclusion, diversity, equality and accessibility (the acronym IDEA) began to infiltrate every aspect of theatre. The theatre was perceived to be run by the white patriarchy, and those people who had previously felt excluded began to push for more IDEA in theatre. Actors’ Equity is an example of a theatre-adjacent organization that was forced to re-consider itself as an organization that had contributed to the exclusion of minorities in its membership, and so chose to open its membership to all actors who basically had ever been paid to act. Casting shows so as to provide more opportunities for minorities to perform became a larger trend than it already had been, but apart from that, placing minorities into positions of leadership became more and more prevalent. The content of plays also began to have a different shape. Plays telling stories from many other cultures and traditions began to appear on stage. Plays by African-Americans, Hispanics, Asians, Native Americans, and other people of color started appearing in theatres.

Lastly, theatrical leadship structures began to change. Broadly speaking, the theatre went from a leadership structure where one person, deemed the “Artistic Director,” decided everything about a theatre’s season, from which plays were done to who directed which plays and what actors might appear in them. Essentially, the Artistic Director was viewed as a (hopefully benevolent, but not always so) autocrat whose word was law. Over the past few years though, that model is being consigned to history, as more and more, leadership at theatres consists of committees of panels or some other communal structure where everyone’s interests are at least heard and considered, if not always put into practice. Artistic directors are not quite ruling the roost as they once did, having in many cases now to answer at least to a panel of some sort so their ideas can gain buy-in from all stakeholders.

None of all this can be said to be the cause of people no longer choosing to attend theatre, but given the large decreases in theatre attendance as surveyed by the SPPA, we should at least understand that all these forces probably play a part in creating a situation where people choose not to attend theatre. Theatre is expensive, and so young people tend to be priced out of the market. Seniors who endured through the pandemic have found other means of entertainment, and with so much entertainment available at home, they are choosing less and less to go out. Seniors are also dying, and young people are not taking their places in the seats. People who view theatre as an opportunity to escape their lives and seek some enjoyment do not want to see IDEA-based politics reflected on the stage. And for the most part, theatre is inaccessible, mostly located in geographic areas where people do not wish to travel or are difficult to get to. Put another way, theatres are generally located in “cultural” areas, and not “community” areas.

I think the best way to describe the present landscape of theatre is that it is struggling. It is struggling internally in terms of finances, leadership, IDEA, and content. It is struggling externally to find an audience that will sustain it financially and culturally. The analogy for my current relationship with theatre is that of two people drowning in the ocean. One is doing their best to calmly stay afloat, while the other is thrashing about in the sea. The one calmly floating is keeping a wary distance from the thrasher, because they know that if they get close and try to save the thrasher, both will drown. Even though I have spent the better part of 50 years participating in the theatre, right now I am keeping my distance for fear of getting caught in the struggle and drowning.

What will become of this struggle? That, I think, is the subject of the next post. If we have at least a broad contour of the present situation, we are in a better position to consider what the future may bring. Hint: I don’t think it will be pretty. -twl

The Summer Theatre Died – Part Three

Dunkirk NY – If you’re one of those persons eager to bootstrap a theatre company, let me just say this – I admire you, and wish you luck. Seriously. The push is on in theatre journalism to report some good news, and there have been a few articles in the major national newspapers from New York, DC, and Chicago touting some good news. American Theatre magazine is also doing its part to paint a rosier picture of the theatrical landscape as we head into 2024. So maybe your plans to start a theatre with some of your friends and colleagues may not be such a bad idea, after all. But please be warned: the odds of starting and sustaining a viable theatre are just as long and just as against you as the odds are of becoming a sustainable working actor.

In this post, I want to examine more closely the relationship between a theatre and its audience by digging just a tad deeper into the demographic information contained in the NEA’s Survey of Public Participation in the Arts (SPPA). A deep look at this data should reveal to us in some measure what the demographic is for a successful theatre, and by extension what the market is for one. Not to give away the ending, but one thing should be immediately clear – theatre is a niche product. It appeals to a small and select group of individuals, and anyone contemplating starting a theatre has at least two choices: tap into the niche demographic, or grow and develop a different one. What we will find in the end is that there is no broad market to tap.

The two charts below will provide us with the data we need. Take a look at them.

![]()

Source: “Arts Participation Patterns in 2022: Highlights from the Survey of Public Participation in the Art”, National Endowment for the Arts

The charts compare the numbers from the 2017 SPPA to the 2022 numbers. The first thing you will notice is that, in the column labeled “Percentage Point Change”, every row has decreased, with the unusual category of ‘Highest Level of Education:Grade School” in the non-musical plays chart going up 0.6 points, from 0.9% to 1.5%. In short, and as noted in Part 2, the market is declining at all levels.

Looking at specific categories and their decline, the ones that stand out most are as follows. Let’s start with attendance at musicals:

- Females dropped from 19.9% to 11.5%, a -8.4 percentage point (pp) decrease.

- Whites dropped from 20.2% to 12.9%, a -7.3 pp decrease.

- Adults 65-74 years of age went from 20.2% to 9.6%, a whopping -10.6 pp decrease

- Adults with graduate degrees dropped from 34% to 20.9%, a -13.1 pp decrease, the largest in this category.

When it came to attendance at non-musical plays, the numbers paint a similar picture:

- The only category to drop double digits was the Graduate Degree category. Those with graduate degrees attending plays went from 21.6% to 10.1%, an 11.5 pp decrease.

- In the Race/Ethnicity category, whites dropped from 11.6% to 5.3%, a -6.3 pp decrease.

- The three sustaining age categories (and by this I mean people who probably have the means to afford theatre tickets) also saw significant drops. 45-54 went from 10% to 4.4% (-5.6 pp); 55-64 went from 9.7% to 3.8% (-5.9 pp); and 65-74 went from 11.5% to 5.2% (-6.3 pp).

And across both musicals and plays, perhaps the most troubling decreases are among college-educated people. I won’t list the numbers here; you can find them on the charts. But the numbers are staggering in their percentage decreases, among the highest percentage point decreases across all categories. College-educated people seem to have stopped attending theatre in droves.

So, if we go down the charts using the 2022 numbers, and pick the highest percentage number out of each category to determine who the best demographic target is for your new theatre, we would want to at the very least try to attract the following audiences:

- For musicals, we would want to attract white females age 25-34 with a college degree, preferably a graduate or professional degree.

- For non-musical plays, it would be a white female age 35-44 with a college degree, preferably a graduate or professional degree. Of significant note, though, is that white females are only one-tenth of a percentage point higher than Black females statistically, as the race/ethnicity category shows African Americans at 5.2% of attendance, and whites at 5.3% of attendance.

In short, if you want to start a successful and sustainable theatre, your best bet is to appeal to professional women age 25-44, programming content that speaks to their lives and issues, and (although I don’t have any data at all for this) also appeals to their children, should they have any. It will pay to be inclusive and diverse in your content and casting. Occasionally it will also pay to produce content for female senior citizens (Menopause the Musical serves as the prime example).

You can, of course, extrapolate from this data, but it’s risky at best. Would rom-coms help bring in more males on dates with their partners? Would LGBTQ+ content expand the audience (one category the SPPA has not seemed to want to touch at all is sexual preference. That data would be most interesting)? Should children’s theatre be an element? Would after school activities that can serve as a daycare service help sustain the bottom line? All these extrapolations, however, maintain the female-centric nature of your theatre. You’re not doing David Mamet any time soon.

As to the actual data itself, there are some things to take into consideration. The first is that the data does not concern itself solely with professionally-produced art. If you went to see your child in their university production of The Glass Menagerie, you could truthfully answer “yes” to the question “did you attend at least one arts event in the past 12 months?” Plays and pageants presented at houses of religious worship count. In short, you did not have to attend a professionally-produced play or musical to answer “yes.”

Another aspect of the survey is that it does not indicate how many people who answered the questions are themselves artists. I have always been interested in trying to find a data set that removes from the data any artists who attend arts events. As an example, in an average theatre audience, if you remove any audience members who are also theatre artists, as well as members of the production’s families and their friends, how many people do you have left in the audience who have no relation at all with anyone connected to the production or the art form? In other words, how many people with no connection at all to the production or the art form professionally bought a ticket? That’s the data I would like to have, and if we had it, I believe the picture would be far more disastrous than it already is. I suspect the largest category of people seeing theatre is theatre people and their family and friends.

I cannot with any degree of certainty say that there are not other niches out there that would do as well. At the community-based level, it is absolutely critical that you do the necessary marketing to find what that niche is. It is not enough simply to say “I want to start a theatre doing XX.” You need to know what the market will support. Personal example: at one point in I believe the mid-90s I was approached about starting a Shakespeare company in my region. The first thing I told the proposed financer was the need to do a market study. We discovered that the region would only support a Shakespeare company if it were located in some proximity to Chautauqua Institution (10 minutes away or less), and we could convince the people there to leave the grounds and attend the shows. I also worked up a first-year capital investment budget, which paid the actors and accounted for technical needs, that came to $30K. The idea soon died, because the market was not there, making a $30K investment (or any investment, for that matter) a waste of money.

In conclusion, there is no broad market for “theatre.” The data points this out quite clearly. The data also points out that the success of building a sustainable theatre that has the capacity to support artists at even a modest standard of living is slim, given the low demand. Your odds of starting and sustaining a theatre are about as great as becoming a Broadway star, which makes either path viable once seen through this prism.

In Part Four, I will speculate as to “what comes next.” The short answer is I’ve no idea. With the data as dismal as it is, with major theatres closing and crumbling, and with interest in theatre within the divided culture we inhabit about as low as it can get, I believe whatever comes next will take several generations to produce. I’ll leave you with this quote from the 2022 SPPA:

At the same time, one should gravely view the overall declines in visual and performing arts attendance, based on the activity types that are listed in the survey. Those activities include art museum or gallery visits, and attendance at jazz, classical, or Latin/salsa music performances, musical and non-musical plays (emphasis mine), craft fairs and outdoor performing arts festivals, opera, and ballet and other dance forms. Ramifications of those declines were still being felt in the summer of 2023, when the closing of many regional theater organizations and shows began to make national news.

-twl

high wind warning

wind against the leaves:

clinging to the branch

desperate to survive

The Summer Theatre Died – Part Two

Dunkirk NY – Of all the pieces of data that exist relative to attendance at performing arts events, none is more comprehensive than the National Endowment for the Arts’ Survey of Public Participation in the Arts (SPPA). Begun in 1982, the SPPA has undergone some changes over the years, and has added categories as new types of arts (mainly digital) were created. Their core “benchmark” categories, however, have remain largely unchanged, and theatre is one of those core benchmarks. What I’d like to do here is give a rough overview of the information contained in the SPPA; I hope a deeper dive will follow once all the supporting data is released. It’s my belief that the data available in this report, which is usually released about every five years, is the most ignored data set among theatre practitioners and theorists today. The NEA just released its summary findings this past October detailing the years from 2017-2022, and as usual, the news is sobering.

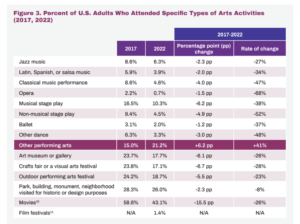

One look at this table might be all you need to grasp the issue:

Source: Arts Participation Patterns in 2022: Highlights from the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts 2022

The basic question asked of participants goes something like this: In the past year, have you attended at least one (insert art event)?. As the table makes clear, from 2017 to 2022, attendance at musical stage plays fell from 16.5% of respondents attending one musical, to 10.3%, a -6.2 percentage point drop, and a -38% rate of change. Non-musical stage plays went from 9.4% to 4.5%, a -4.9 percentage point drop, and a -52% rate of change. People continue to abandon theatre-going as a cultural activity.

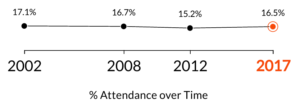

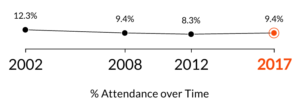

Now, I realize these numbers are raw. They tell us attendance is dropping, but they do not tell us why. And we also know that this survey data takes in the worst of the pandemic years, when theatres across the country shut down. So the data might possibly be skewed a bit, and may not be representative of actual trends. But you can also look at these two timeline graphs, which show the percentages from 2002-2017:

Musical Stage Plays

Non-musical Stage Plays

The numbers were always low, but with the 2022 data, the numbers have never been lower. 2017 was a banner year that seemed to stop the bleeding a little bit, but the trend has always been downward.

What to make of this broad data? If we think of theatre as a marketplace commodity, then the most obvious conclusion is that, for whatever reason, the market is drying up. If theatre is to be sustainable, and if we want artists to be able to create sustainable lifestyles through their art, then there must, first of all, be a market (and hopefully a growing one) for their product. But the data says, at this point in time, there is virtually no market, and whatever market is left is shrinking rapidly. If you don’t have a market for your services/theatre, then the question of building a sustainable theatre endeavor is moot, or at the very best, foolhardy.

To put it plainly, theatre is dying because the market for theatre is dying. All the theatres that closed or reduced their seasons over the summer have clearly seen the writing on the wall. Theatres that have remained open have, on the whole, yet to recover to their pre-pandemic numbers. In a stagnant and shrinking market, it is clearly an immense challenge to think about creating a sustainable career in theatre, no matter how you go about doing it. Theatre is in an entropic spiral, and usually when that occurs, it’s best to let the spiral take its course, much like the best option when fighting a forest fire is simply to let itself burn out.

I want to keep this post relatively short so as to lay a foundation for a closer look at the SPPA data. Probably after the Thanksgiving holiday I’ll get another post written that will take a look at the demographic data contained in the report. In the meantime, if you’d like to get a jump on that post, you can find the 2023 SPPA Summary report on the NEA website. -twl